- Funs Jacobs

- Posts

- The Most Important Company in the World

The Most Important Company in the World

The unbelievable journey from failed gaming chip to defining the direction of human progress.

From Gaming Chips to Global Power: The Nvidia Story

Who remembers the days when all big companies started shouting that data is the new oil, the new gold. Every big brand wanted to collect as much data as company, with of course the leading big tech (and especially social) companies leading the way.

Why? Because the more data you have on a person, the higher the chances that you will sell this person something. That, plus data meant power. Just like oil gives countries exactly that. Little did we (or at least I) know then, that there was something else that would become far more valuable only a few years later: compute.

That is what I would like to talk to you about today, a deep dive in one of the most important companies (if not the most important company) in the AI era: Nvidia. Let’s look at how they started, why they are so important, the landscape and the future. So much to share so let’s dive in!

Humble beginnings, the Jensen Huang story

Nvidia might be one of the most recognizable brands out there at the moment and that isn’t normal for a computer hardware company 🤣. I personally got introduced to Nvidia years ago when I wanted to get back to gaming on PC’s, after switching to console. It was clear that there was only one processor you needed to have and that was an Nvidia GPU. Not AMD, not Intel, but the very specific apple green of Nvidia.

A few years ago I was a speaker at the IBC Conference at the RAI Amsterdam and that day we were running with a whole crew of Nvidia people, as we were partnering with them for multiple reasons with Media.Monks. These guys were being followed and almost “harassed” by so many people because they were wearing either a badge or shirt with the Nvidia logo. True superstars, kinda funny to see.

But the story of Nvidia started with one man, it’s founder and still CEO, Jensen Huang. Probably one of the most defining CEO’s of our time.

Young Jensen Huang as an engineer

Jensen Huang’s path to Nvidia was shaped long before the company existed. Born in Taiwan, raised in Thailand and later the United States, he grew up without the advantages most Silicon Valley founders enjoy. He lived with relatives, cleaned toilets at a Denny’s, and worked his way into electrical engineering at Oregon State before completing his master’s at Stanford. What he did have was an obsession with how computers worked and a talent for spotting patterns early. His years at LSI Logic and AMD exposed him to the limits of the semiconductor industry. CPUs were the center of the computing universe at the time. Every major machine ran on them. But by the early nineties it was obvious that the old model was hitting a wall. CPUs excelled at doing one task very quickly. They were never designed to handle the rising demands of parallel workloads. And nothing pushed hardware harder than graphics.

3D gaming was about to explode, and rendering those worlds required a different kind of compute. Instead of processing instructions one by one, the future needed chips that could execute thousands of operations at the same time. Huang recognised this long before it became mainstream thinking. He understood that visual computing wasn’t just entertainment. It was a preview of where digital experiences were heading. Richer. More immersive. More computationally intense. And the industry had no architecture built for it.

That insight is what led Huang to co-found Nvidia in 1993. A company built on the belief that the next era of computing would be powered by parallel processors designed for graphics first, and eventually for everything else. Nvidia wasn’t created for AI. It wasn’t created for data centers.

Jensen Huang and his now famous leather jacket presenting their latest product.

Jensen Huang didn’t build Nvidia alone. He founded it in 1993 with two key partners.

He teamed up with Chris Malachowsky and Curtis Priem. Both were seasoned engineers with deep expertise in graphics and system architecture.

• Chris Malachowsky came from Sun Microsystems, where he worked on high-performance systems. He brought the engineering discipline and systems thinking that helped Nvidia survive its early, chaotic years.

• Curtis Priem was one of the most talented GPU architects of his generation. He designed the first graphics processor for the IBM PC and had a track record of pushing boundaries in visual computing.

Huang provided the vision and the long-term technical instinct.

Malachowsky provided operational and system-level strength.

Priem brought cutting-edge graphics design.

Together, the trio built Nvidia around the belief that graphics would transform computing. And the traditional CPU world was not ready for what was coming.

It all started with: Gaming.

Nvidia didn’t become a powerhouse overnight. Their first product, the NV1, was actually a failure. It was a strange hybrid card that tried to do everything at once. 2D graphics. 3D graphics. Audio. Even Sega Saturn controller support 🤣. It launched in 1995 and the market rejected it immediately. Developers didn’t want a chip that went in every direction. They wanted one that solved a single problem extremely well.

Nvidia almost died after this complete failure. But this failure shaped something essential in their culture. Brutal focus. Fast iteration. A willingness to throw out bad ideas quickly and rebuild from scratch. That mindset is what saved them.

Only one year later they released the RIVA 128, and this time they got it right. It was fast, simple, and built specifically for 3D graphics at a moment when gaming was shifting into full 3D worlds. Developers loved it. Gamers loved it.

But the real breakthrough came in 1999 with the GeForce 256. Nvidia called it the world’s first GPU. Not just a graphics card. A graphics processing unit. A new category of compute. The card handled geometry transformations and lighting directly on the chip, which took huge pressure off the CPU and unlocked a new level of visual fidelity. Games started looking and feeling like entirely new worlds. For the first time, GPUs weren’t just rendering pixels but were doing real, heavy computation.

And this was the moment Nvidia pulled ahead of everyone else, at one hand because of engineering, but on the other hand also because of strategy. They didn’t just make chips. They invested deeply in the entire development ecosystem. Tools, documentation, SDKs, drivers, support. They made it easy for every game studio on earth to build for Nvidia hardware. This is the same playbook they would later use for AI. Hardware alone isn’t enough. You need the whole ecosystem.

Nvidia had found its first engine. Gaming proved that Huang’s original hypothesis was right. Parallel compute was the future. The world wanted richer digital experiences. And Nvidia was the only company building silicon powerful enough to deliver them.

This set the stage for something nobody saw coming. Their chips were about to become valuable for something far bigger than rendering game worlds.

A new digital economy was about to knock on the door.

The Bitcoin mining boom

Nvidia built its reputation on gaming, but the company’s next growth wave came from a place nobody in Silicon Valley expected. Cryptocurrency.

In the early 2010s, Bitcoin mining was still something you could do on a normal computer. At first, miners used CPUs. Then they realised something obvious in hindsight. Mining is a massively parallel workload. CPUs are built for sequential logic. GPUs are built for parallel throughput. Which means that GPUs weren’t just better for mining. They were orders of magnitude better.

Almost overnight, Nvidia cards stopped being gaming hardware and became financial infrastructure.

Miners were buying out entire inventories of GeForce GPUs, sometimes straight from warehouses, creating a strange new global dynamic. Cards meant for gamers were suddenly being stacked in basements and data centers to extract digital currency. Prices skyrocketed. Scarcity became a constant. Nvidia saw quarter after quarter of unpredictable demand spikes that had nothing to do with the gaming industry they originally built for.

Bitcoin mining started as a fun individual hobby but turned into massive billion dollar businesses.

This period taught Nvidia two important lessons.

First, their chips had far more value than they originally assumed. A GPU wasn’t a graphics accelerator. It was a general-purpose compute engine that could fuel entirely new economies. Bitcoin was the first proof of that. A completely new financial system emerged, and GPUs became the picks and shovels.

Second, the company learned what it meant to be a supplier to a market they didn’t control. Crypto demand was volatile. It moved fast. It broke supply chains. It pushed Nvidia into situations where gamers were angry, miners were hoarding cards, and quarterly guidance became a guessing game. Huang responded the same way he always did. He adapted. Nvidia introduced mining-specific products, changed distribution strategies, and got more aggressive in shaping demand.

But the most important outcome of the mining boom wasn’t financial. It was conceptual. Nvidia now understood, in a very real way, that the GPU had become a universal compute engine. A piece of silicon powerful enough to drive virtual worlds, digital currencies and, soon, something much bigger.

Because while miners were filling warehouses with GeForce cards, researchers in another corner of the world were discovering that these same GPUs were the perfect engines for training neural networks.

The next revolution was already brewing. And Nvidia was standing right in the center without even knowing it yet.

From GPUs for Gaming to GPUs for intelligence.

If gaming validated Nvidia’s architecture and crypto exposed its economic power, AI is where everything converged. This is the moment Nvidia went from a successful hardware company to the backbone of the most important technological shift since the birth of the internet.

Back in 2006, Nvidia launched CUDA, a software layer that allowed developers to repurpose GPUs for general-purpose computing. It was originally aimed at scientists and researchers working on simulations. Nothing about AI. Nothing about training models. Just more flexibility for parallel compute.

But that decision quietly set the entire future of Nvidia in motion.

By the early 2010s, a handful of researchers started experimenting with CUDA for neural networks. And then everything changed in 2012.

That year, Alex Krizhevsky, a Canadian computer scientist, teamed up with Ilya Sutskever and their advisor Geoffrey Hinton at the University of Toronto. (Sounds familiar? We talked about this moment with Geoffrey Hinton, aka the Godfather of AI, in our Google deep dive as well). Together they built AlexNet, a deep neural network that crushed the ImageNet visual recognition competition. The key part. They trained the entire model on just two Nvidia GeForce GPUs. It wasn’t a supercomputer. It wasn’t a data center. It was two consumer cards that anyone could buy.

This result flipped a switch across the AI community. Until that moment, neural networks were mostly trained on CPUs. Slow. Expensive. Painful. AlexNet proved something the industry couldn’t ignore. GPUs were the perfect engines for deep learning. Parallel compute was the missing ingredient.

That single breakthrough, powered entirely by Nvidia hardware, revolutionized modern AI research and opened the path to every major model we use today.

After that, everything accelerated.

Deep learning moved from research labs into every tech giant. The first wave of AI startups emerged. Companies began buying GPUs in bulk. Nvidia responded with a speed no competitor could match. New architectures. New form factors. New software tools. A shift from consumer cards to full data center compute platforms.

The A100 launched in 2020. The H100 in 2022. Each one became the new global baseline for AI capability.

If you want to train the next frontier model today, you need thousands of Nvidia chips. If you want to deploy AI at scale, you need Nvidia’s inference performance. If you want to build a new model architecture, you need CUDA. Nvidia has become the technical, economic and cultural center of the AI world.

What started as a graphics company now controls the most important compute layer of our time. Not because they out-marketed the competition. But because they spent decades building the perfect architecture, the perfect ecosystem and the perfect software stack at exactly the moment AI needed it.

The GPU stopped being a gaming engine. It became an intelligence engine.

And the rest of the world is still trying to catch up.

The magic triangle. Nvidia . TSMC . ASML

To understand the era of AI compute, you have to understand the infrastructure that makes it possible. Three companies sit at the core of this system. Not by strategy. Not by design. Simply because each one solved a problem so difficult that no one else could.

Together they form the triangle that underpins nearly every advanced chip in the world.

Nvidia. The architect.

Nvidia controls the design and the entire software ecosystem around its GPUs. CUDA, drivers, tooling. This lock-in is a strategic moat. But Nvidia doesn’t produce a single chip itself.

TSMC. The builder.

Every advanced Nvidia GPU is manufactured by TSMC in Taiwan. They run the world’s most sophisticated chip fabrication processes. Without TSMC’s leading-edge nodes, no H100s, no Blackwell, no next-gen AI acceleration. This places a massive geopolitical spotlight on Taiwan, because the entire AI industry depends on its stability.

ASML. The enabler.

TSMC can only produce chips at this scale because of ASML. The Dutch company builds the world’s only EUV lithography machines. Without EUV, no advanced semiconductors exist. There is no second supplier. No backup. No replacement.

ASML engineers walk past a High NA EUV tool at ASML’s headquarters in Veldhoven, Netherlands.

That is the triangle. Not a symbol of dominance. A map of dependency.

And the risk is simple. If any corner of this triangle fails—politically, economically or technologically—the entire global compute landscape stalls instantly.

Every advanced GPU, every frontier AI model and every breakthrough in compute sits on top of this fragile foundation.

The rise of competitors. The scramble to diversify compute

As AI demand exploded, the industry realized something obvious and uncomfortable. Relying on a single company for the world’s compute supply isn’t sustainable. This didn’t spark a “kill Nvidia” movement. It sparked a push for independence.

Interestingly enough though, the best AI models on the market today are not trained on Nvidia GPUs. Enter Google.

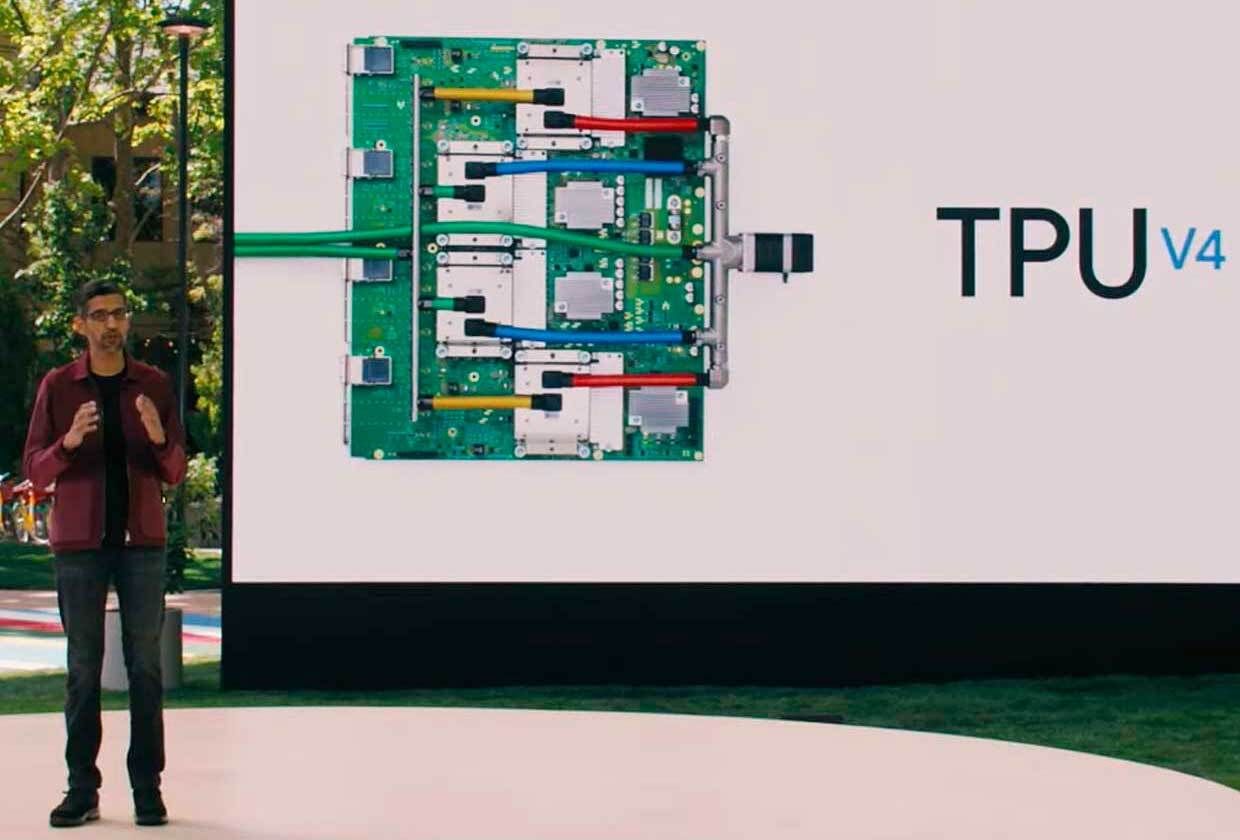

Google realised early that CPUs and generic hardware couldn’t handle the scale of its machine-learning workloads, so they built their own chips. Their TPUs have powered every major Google model for years, including the latest Gemini Ultra. In other words, Google never relied on Nvidia in the first place.

Google never sold their TPUs to other companies, until now. Anthropic is training large models on TPU v5p clusters, and Meta is exploring multi-billion-dollar TPU deals. Not because they want to copy Google, but because Google proved that world-class AI can run entirely on a different compute ecosystem. And maybe a bit to be less dependent on Jensen Huang?

Beyond Google, the rest of the industry is also moving fast to build alternatives. AWS just announced a new generation of its own AI chips, Trainium2 and Inferentia3, built to lower the cost of training and running models for customers who don’t want to depend solely on Nvidia’s supply chain. Intel is taking a different route. Backed heavily by the US government, it’s being positioned as a strategic pillar in the geopolitical AI race, with the goal of rebuilding domestic manufacturing capacity and reducing America’s reliance on Taiwan. These developments don’t threaten Nvidia’s leadership, but they do signal a clear shift. The world wants more compute options. More sovereignty. More resilience. And the race to build them has officially begun.

Closing thoughts

Nvidia’s rise is nothing short of historic. It became the first company in history to cross five trillion dollars in valuation and is now the most valuable company on the planet. That alone tells you something. Compute has become the defining resource of our time, and Nvidia sits right at the center of it.

Competition is rising. Google with TPUs. AWS with Trainium. AMD with MI300. Intel backed by the US government. And that’s a good thing. The world needs far more compute than one company can ever supply. Jensen Huang said it himself. Every increase in compute capacity unlocks new applications, new industries and new forms of intelligence that will eventually benefit all of us. The demand curve isn’t slowing. It’s compounding.

A more distributed landscape of compute providers is not just healthy. It’s necessary. Partly because the appetite for compute will remain immense. But also because the current dependency chain is too fragile. Nvidia designs the chips. TSMC builds them. ASML enables the entire process. One shock in that system. political or technical. can disrupt the global AI ecosystem overnight.

And even beyond chips, the real bottleneck isn’t silicon. It’s energy. Training and running AI at the scale we’re heading toward requires industrial levels of power. If we want intelligence to scale, we need breakthroughs in how that power is produced. Nuclear fission, nuclear fusion, next-generation reactors. This space is moving fast and it will shape the limits of AI far more than most people realise. China is already far ahead of the United States in reactor deployment. The race is on.

This is no longer just a technology story. It’s a geopolitical one. Who can generate the most energy. Who can build the most compute. Who can secure the supply chains that shape the future of intelligence.

We are witnessing the opening chapters of a global power shift that will define the next century. And the fascinating part. We’re still only at the beginning.

PS... If you’re enjoying my articles, will you take 6 seconds and refer this to a friend? It goes a long way in helping me grow the newsletter (and help more people understand our current technology shift). Much appreciated!

PS 2... and if you are really loving it and want to buy me some coffee to support. Feel free! 😉

Shoppers are adding to cart for the holidays

Over the next year, Roku predicts that 100% of the streaming audience will see ads. For growth marketers in 2026, CTV will remain an important “safe space” as AI creates widespread disruption in the search and social channels. Plus, easier access to self-serve CTV ad buying tools and targeting options will lead to a surge in locally-targeted streaming campaigns.

Read our guide to find out why growth marketers should make sure CTV is part of their 2026 media mix.

Your readers want great content. You want growth and revenue. beehiiv gives you both. With stunning posts, a website that actually converts, and every monetization tool already baked in, beehiiv is the all-in-one platform for builders. Get started for free, no credit card required.

Thank you for reading and until next time!

Who am I and why you should be here:

Over the years, I’ve navigated industries like advertising, music, sports, and gaming, always chasing what’s next and figuring out how to make it work for brands, businesses, and myself. From strategizing for global companies to experimenting with the latest tech, I’ve been on a constant journey of learning and sharing.

This newsletter is where I’ll bring all of that together—my raw thoughts, ideas, and emotions about AI, blockchain, gaming, Gen Z & Alpha, and life in general. No perfection, just me being as real as it gets.

Every week (or whenever inspiration hits), I’ll share what’s on my mind: whether it’s deep dives into tech, rants about the state of the world, or random experiments that I got myself into. The goal? To keep it valuable, human, and worth your time.

Reply